Hubble Uncovers Concentration of Small Black Holes

stsci_2021-08a February 11th, 2021

Credit: Image: NASA, ESA, T. Brown, S. Casertano, and J. Anderson (STScI) Science: NASA, ESA, and E. Vitral and G. Mamon (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris)

The idea that black holes come in different sizes may sound a little odd at first. After all, a black hole by definition is an object that has collapsed under gravity to an infinite density, making it smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. But the amount of mass a black hole can pack away varies widely from less than twice the mass of our Sun to over a billion times our Sun's mass. Midway between are intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) weighing roughly tens of thousands of solar masses. So, black holes come small, medium, and large.

However the IMBHs have been elusive. They are predicted to hide out in the centers of globular star clusters, beehive-shaped swarms of as many as a million stars. Hubble researchers went hunting for an IMBH in the nearby globular cluster NGC 6397 and came up with a surprise. Because a black hole cannot be seen, they carefully studied the motion of stars inside the cluster, that would be gravitationally affected by the black hole's gravitational tug. The shapes of the stellar orbits led to the conclusion that there is not just one hefty black hole, but a swarm of smaller black holes – a mini-cluster in the core of the globular.

Why are the black holes hanging out together? A gravitational pinball game takes place inside globular clusters where more massive objects sink to the center by exchanging momentum with smaller stars, that then migrate to the cluster's periphery. The central black holes may eventually merge, sending ripples across space as gravitational waves.

Provider: Space Telescope Science Institute

Image Source: https://hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2021/news-2021-008

Curator: STScI, Baltimore, MD, USA

Image Use Policy: http://hubblesite.org/copyright/

- ID

- 2021-08a

- Subject Category

- B.3.6.4.2

- Subject Name

- NGC 6397

- Credits

- Image: NASA, ESA, T. Brown, S. Casertano, and J. Anderson (STScI) Science: NASA, ESA, and E. Vitral and G. Mamon (Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris)

- Release Date

- 2021-02-11T00:00:00

- Lightyears

- 9,000

- Redshift

- 9,000

- Reference Url

- https://hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2021/news-2021-008

- Type

- Observation

- Image Quality

- Good

- Distance Notes

- Facility

- Hubble, Hubble

- Instrument

- ACS/WFC, ACS/WFC

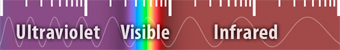

- Color Assignment

- Cyan, Orange

- Band

- Optical, Optical

- Bandpass

- B, V

- Central Wavelength

- 435, 625

- Start Time

- Integration Time

- Dataset ID

- Notes

- Coordinate Frame

- ICRS

- Equinox

- 2000.0

- Reference Value

- 265.16703836449, -53.66992797621

- Reference Dimension

- 2462.00, 1847.00

- Reference Pixel

- 1427.45804808755, 1039.71204885490

- Scale

- -0.00002225409, 0.00002225409

- Rotation

- 0.12661082060

- Coordinate System Projection:

- TAN

- Quality

- Full

- FITS Header

- Notes

- World Coordinate System resolved using PinpointWCS 0.9.2 revision 218+ by the Chandra X-ray Center

- Creator (Curator)

- STScI

- URL

- http://hubblesite.org

- Name

- Space Telescope Science Institute Office of Public Outreach

- outreach@stsci.edu

- Telephone

- 410-338-4444

- Address

- 3700 San Martin Drive

- City

- Baltimore

- State/Province

- MD

- Postal Code

- 21218

- Country

- USA

- Rights

- http://hubblesite.org/copyright/

- Publisher

- STScI

- Publisher ID

- stsci

- Resource ID

- STSCI-H-p2108a-f-4924x3693.tif

- Resource URL

- https://mast.stsci.edu/api/latest/Download/file?uri=mast:OPO/product/STSCI-H-p2108a-f-4924x3693.tif

- Related Resources

- Metadata Date

- 2021-02-09T11:09:40-05:00

- Metadata Version

- 1.2

Detailed color mapping information coming soon...